Financial markets—specifically derivatives—contain information about the range of probable future short-term interest rates. The information from this statistical distribution can help measure the perceived risk of interest rates returning to the zero lower bound in the future. The risk varies over time, driven mainly by the expected level of interest rates. At longer forecast horizons, a higher risk of returning to the lower bound primarily reflects a higher amount of uncertainty. Currently, the perceived risk appears slim over the next few years but is significant at longer horizons.

Interest rates have fluctuated significantly over time. After a period of high inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, interest rates entered a decline that lasted for nearly four decades. The federal funds rate—the primary tool for monetary policy in the United States—followed this trend, while also varying with cycles of economic recessions and expansions.

By the late 1990s, interest rates had declined to the point that researchers began discussing concerns about hitting the zero lower bound (ZLB)—meaning the policy rate could not fall further to stimulate the economy if needed. However, it was not until December 2008, at the height of the Great Recession, that the bottom of the target range for the federal funds rate reached the ZLB, where it remained until December 2015. After about four years of higher rates, the federal funds rate dropped to the ZLB again to ease economic conditions at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to a surge in inflation, the Federal Open Market Committee lifted the federal funds rate in March 2022 and has since kept it a sizable distance above the ZLB.

This Economic Letter examines to what extent markets are concerned that policy might return to being constrained by the ZLB at some future date. We use financial market prices to study how changes in the outlook for interest rates and the uncertainty surrounding that outlook affect the perceived risk of returning to the ZLB. Our approach relies on the forward-looking nature of asset prices, which reflect both medium-term cyclical developments and longer-run structural factors that shape the future path and uncertainty of interest rates (see, for example, Bauer and Christensen 2014 and Bauer and Mertens 2019).

Uncertain interest rates

Our analysis focuses on interest rate derivatives tied to the future evolution of a key short-term interest rate, either LIBOR or SOFR. SOFR tends to comove closely with the federal funds rate, and other short-term interest rates tend to move in tandem with it. SOFR has replaced LIBOR as the primary benchmark short-term rate in U.S. financial markets, and a wide range of SOFR-based interest rate derivatives are traded. Among these derivatives are futures and swaps that allow us to extract the expected path of LIBOR through the end of 2021 and of SOFR since 2022 at various forecast horizons as well as interest rate caps, which can be priced as a portfolio of options and reflect the uncertainty surrounding the expected path.

We use these financial market prices to estimate perceived probability distributions for future short-term interest rates on each trading day. Our methodology follows Mertens and Williams (2021), where the expected level and uncertainty of future interest rates are captured through a normal distribution. We impose the ZLB by truncating the distribution such that otherwise negative realizations of future interest rates appear as zero. Note that we do not adjust the distributions for risk premiums that investors might demand as compensation for taking on risk.

Figure 1 shows the baseline estimated probability distribution of seven-year-ahead short-term interest rates on May 27, 2025 (blue curve), along with two hypothetical distributions (green and red curves), represented by their densities. The dashed lines represent the portions of the underlying normal distributions that would result in negative interest rates and are thus truncated at zero in our estimates. The probability of reaching the ZLB in our baseline estimated distribution therefore coincides with the probability of negative interest rates in the underlying distributions. We refer to this probability as the ZLB risk. On May 27, seven-year-ahead ZLB risk stood at about 9%.

Figure 1

Effect of expected interest rates & uncertainty on ZLB risk

Source: Bloomberg and authors’ calculations.

To demonstrate how ZLB risk responds to changes in the expected level of interest rates and uncertainty, we vary the baseline distribution through two hypothetical scenarios. The green hypothetical distribution has a lower expected level of interest rates, captured by the average of the distribution, but the same amount of uncertainty, captured by the variance across the distribution. In this case, the distribution retains its exact shape and shifts to the left. As a result, the likelihood that interest rates get truncated at zero increases, raising ZLB risk. The red hypothetical distribution keeps the same expected level but reflects a higher amount of uncertainty. As a result, the distribution curve widens, again increasing the likelihood of interest rates reaching the ZLB, similar to the results in Bok, Mertens, and Williams (2025). The hypothetical distributions are calibrated such that they imply the same ZLB risk. In summary, the figure demonstrates that ZLB risk rises with either a decrease in the expected level of interest rates or an increase in uncertainty.

ZLB risk over time

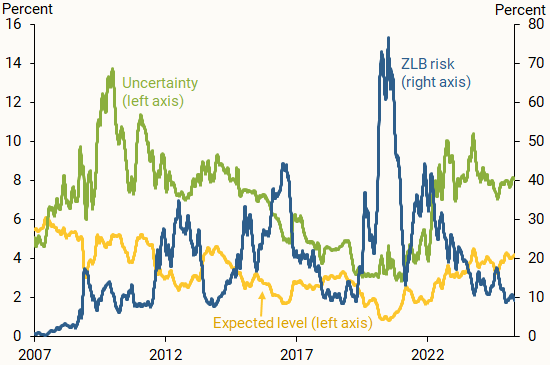

We use price data for derivatives from January 2, 2007, to May 27, 2025, to construct a daily time series of ZLB risk for a range of forecast horizons. Figure 2 shows seven-year-ahead ZLB risk, along with the corresponding expected level of interest rates and uncertainty, using 20-day moving averages of the daily time series.

Figure 2

Expected level of interest rates, uncertainty, and ZLB risk

Source: Bloomberg and authors’ calculations.

The expected level of interest rates has changed over time, tracking movements in the federal funds rate. It declined steadily from about 6% in 2007 to around 1% after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, it has gradually increased, hovering around 3–4% since 2023. Uncertainty has also fluctuated, typically rising during periods of economic stress or major shifts in monetary policy. Uncertainty spiked following the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic and has remained elevated since.

The expected level of interest rates and uncertainty surrounding it tend to comove positively, as seen in Figure 2, with a correlation of 0.64. Theoretically, this comovement has ambiguous implications for ZLB risk: While a higher expected interest rate level decreases the probability of reaching the ZLB, a higher uncertainty increases it. Empirically, shifts in the expected level of interest rates appear to be the primary driver of changes in ZLB risk. Currently, seven-year-ahead ZLB risk is comparable to that observed in 2018, even though the expected interest rate level is higher. This reflects that uncertainty is higher today than it was in 2018.

Drivers of ZLB risk

Figure 3 confirms that the expected level of interest rates is a key driver of variation in ZLB risk over time. The figure shows a scatterplot of the seven-year-ahead expected level of interest rates on the horizontal axis and the corresponding ZLB risk on the vertical axis, using monthly averages from January 2007 to May 2025. The downward curve in the data shows that the relationship is strongly negative and nonlinear: As the expected level declines, ZLB risk rises—particularly sharply for expected levels below 2% on the left side of the figure.

Figure 3

Expected level versus ZLB risk: January 2007 to May 2025

Source: Bloomberg and authors’ calculations.

This nonlinearity arises naturally from the truncated distribution. With interest rates limited to not fall below zero, the probability of reaching the ZLB in the future rises rapidly as the expected level approaches 0%. Conversely, as expected rates rise to higher levels, the probability of being at the ZLB slowly approaches zero.

The red diamond in the figure represents the most recent reading in our data set from May 27 2025, with a seven-year-ahead expected level of about 4% and a ZLB risk of about 9%. This is consistent with the historical relationship, as the red diamond lies directly on the curve.

The term structure of ZLB risk

Figure 4 shows the term structures of ZLB risk, the expected level of interest rates, and uncertainty across forecast horizons ranging from 2 to 10 years, reported on May 27, 2025. The term structure of ZLB risk refers to the probability of being constrained by the ZLB at the end of each forecast horizon.

Figure 4

Term structures of ZLB risk, expected level, and uncertainty

The recent term structures of ZLB risk and uncertainty in the figure reflect a broadly representative pattern. When the current interest rate is well above the ZLB, the term structure of ZLB risk tends to be upward-sloping, meaning that the probability of being constrained by the ZLB mostly increases with the length of the forecast horizon. Similarly, the term structure of uncertainty is upward-sloping, meaning that longer-horizon interest rate forecasts are less precise than shorter-horizon forecasts. As Figure 1 demonstrated, this increase in uncertainty raises ZLB risk. Current market pricing differs somewhat in that the expected level of interest rates is roughly constant across forecast horizons. At times when policy is already at the ZLB, near-term ZLB risk might be elevated to a degree that the term structure becomes downward-sloping.

With an expected level of interest rates around 3–4%, the perceived risk of returning to the ZLB over the next two years is about 1%. This risk increases to about 9% at the seven-year horizon and remains at similar levels over longer horizons. To put the current term structure into context, medium- to long-term ZLB risk is currently at the lower end of the range observed over the past 15 years. The last time seven-year-ahead ZLB risk reached a similar level was in 2018. But the composition of ZLB risk has changed since then: While the expected level of interest rates at the seven-year horizon is about a full percentage point higher than in 2018, the current considerably elevated uncertainty offsets it and results in a comparable likelihood of reaching the ZLB. Updates related to the term structure of ZLB risk and the time series for different horizons are available on the San Francisco Fed’s Zero Lower Bound Probabilities data page.

Conclusion

Financial market derivatives provide real-time forward-looking measures of the perceived risk of reaching the zero lower bound in the future. This ZLB risk tends to fall with higher expected levels of interest rates and tends to rise with interest rate uncertainty. Compared with the past decade, current data show that expected levels of future interest rates are high. Nevertheless, ZLB risk remains significant over the medium to long term, similar to levels observed in 2018, due to recent elevated uncertainty.

Published concurrently on Liberty Street Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

References

Bauer, Michael D., and Jens H.E. Christensen. 2014. “Financial Market Outlook for Inflation.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2014-14 (May 12).

Bauer, Michael D., and Thomas M. Mertens. 2019. “Zero Lower Bound Risk according to Option Prices.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2019-24 (September 23).

Bok, Brandyn, Thomas M. Mertens, and John C. Williams. 2025. “Macroeconomic Drivers and the Pricing of Uncertainty, Inflation, and Bonds.” FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2022-06, revised April 6, 2025.

Mertens, Thomas M., and John C. Williams. 2021. “What to Expect from the Lower Bound on Interest Rates: Evidence from Derivatives Prices.” American Economic Review 111(8), pp. 2,473–2,505.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to research.library@sf.frb.org